" 'I never saw anybody that looked stupider', a

Violet said, so suddenly, that Alice quite

jumped..."In looking Glass, Lewis Carroll attributes

to this flower a far more caustic tongue than I would have

expected after looking closely at their faces.

Now, and I don't know how it's happened, violas and

pansies have appeared like a deep indigo dye soaking

through the pages of this book. Ought I to apologize

because there they come again? Perhaps it's because the

flowers are universally available with their familiar demeanor,

and maybe too because they are found in natural habitats

as diverse as the blandly pastoral and the raw

wilderness.

They are flowers to which there has to be some sort of

response, however dedicated to the smell of diesel oil

and the thrum of machinery a person indifferent to flora

and fauna may be. As there are about twenty-two genera

and well over nine hundred species of Violaceae

worldwide, it's not surprising that we make strong and

personal judgment about these flowers. I know I have

written about violets, violas, and pansies earlier in

the book, including those aberrations, those nightmare

mutations bred for show with faces and purple patches

too heavy to remain vertical without support, but now I

want to write about the species of this genus: the

source of all the hybrids we buy by the fistful each

spring and autumn.

Violets have been with us for thousands of years, and

but for them, and for their continuing existence, we

would never have the annual treat of stocking our

flowerbeds from seeds and nurseries with members of this

motley clan just as demurely or as flamboyantly as we

choose. Lose the wild flowers, and we would lose our

source of renewal.

|

|

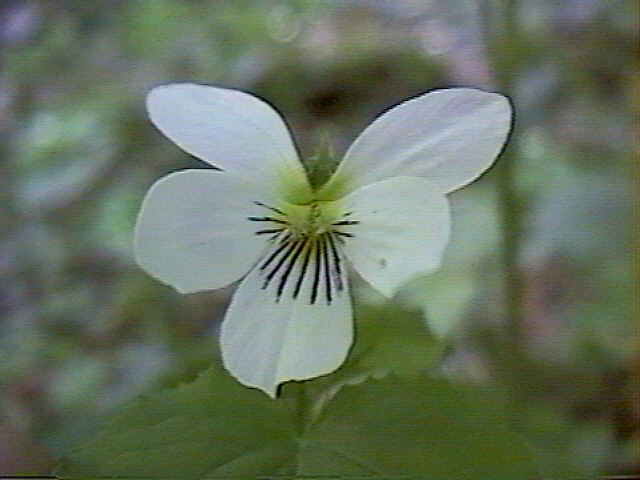

Viola Canadensis

|

In America, at the end of the last century, New England

was the Mecca of violet growing, and, as in London,

violets were sold on the streets of New York. Natives of

the violet family, such as Viola blanda,

are still to be found in the United States from Maine to

Georgia. V. canadensis is an herb of the

eastern seaboard and the Rockies, while a tall, striped

viola, V. striata, and the large-bloomed

Great American Violet, V. cucullata, are

found in the far north of the continent.

In the Olympic National Park in the state of Washington

are found three of the most lovely violas: the hook

violet, the pioneer violet, and the Flett Violet.

|

|

Hook Violet (Viola adunca)

|

The hook violet, V. adunca, a low,

deep blue flower with a white heart, and the tall pioneer

violet, V. glabella, a brilliant

yellow flower with heart-shaped leaves and purple

"honey guides," both grow in the impenetrable

forest, where openings of the tree canopy allow enough

sunlight through, and also in the sub-alpine zone

(similar to the sub-artic regions of Canada), where the

growing season is short and where, in midsummer, there

are moist meadows and dry hillsides. The hook violet is

also widespread in the temperate parts of North America

and the pioneer violet is found in southern Alaska and

the Sierra Nevada.

The third of these violas is rare: the Flett violet,

V. flettii, is bluish-purple and only

appears in the high country after the last snow has

melted among rocky crevices of the peaks on the south

and west-facing slopes. The Flett violet is among seven

other plants endemic to the Pleistocene Ice Age.

Glaciers, about three thousand feet deep, left isolated

peaks rising above frozen desolation, and where these

eight relics have miraculously survived.

The violet family are promiscuous; given the chance,

they would inveigle us to sigh over their frailty

throughout north European countries and Greenland, the

Mediterranean, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Syria,

Palestine, and North Africa; on through Kashmir, the

Atlas mountains, and the Himalayas, to Central Siberia

and the Altai mountains; and improbable as it may seem

the marsh violet inhabits the Azores.

For the following information on the thirteen species

indigenous to Britain I am unequivocally indebted to a

friend and botanist, Jo Dunn. Without her painstaking

field work and research as well as her scholarly notes,

photographs, and patient guidance, I should be wallowing

in a sea of violets, unable to disentangle one tiny

flower from another.

|

|

Early Dog Violet |

Here are their Latin names for those in the know or on

the brink of becoming that way: Viola odorata

(sweet violet); V. hirta (hairy violet); V.

rupestris (Teesdale violet); V. riviniana

(common dog-violet); V. reichenbachiana

(early dog-violet); V. canina (heath

dog-violet); V. lactea (pale dog-violet); V.

persicifolia (fen violet); V. palustris

(marsh violet); V. lutea (mountain pansy);

V. tricolor (wild pansy but also known as

heartsease); V. tricolor subspecies curtisii

(dune pansy): V. arvensis (field pansy)'

and V. kitaibeliana (dwarf pansy).

Starting with the sweet violet, this one appears

early in the year with a span of colour varying from

deep purple, through lilac and rosy-mauve to white and

it's the only one of our violets that is scented. How

surprising when you think now often we associate these

flowers with fragrance. The sweet violet lurks; scrub,

hedgerows, or woodland are its territory as well as

chalky soil. IN country churchyards where it may occur

naturally or may have been deliberately introduced from

gardens or countryside, it remains safe from

annihilation by the manic use of herbicides which still

pollutes even some of our graveyards. As summer

progresses reproduction of the sweet violet is either by

self-pollination or by means of "stolons," the

surface runners, rather as strawberries take root.

The scentless hairy violet in shades of shadowy

blue-violet veined with purple, is as beautiful as any

in this country. Found in open, calcareous grassland it

is clumpy in growth with a creamy eye and leaves that

when young scroll inwards the way some shells are

devised. The hairiness comes from the roughness of the

leaves and dense hairs on the leaf-stalks, which make it

easy to distinguish from the sweet violet. Instead of

runners, it has seeds and seed-stalks rich in oil. Jo

tells me she has found young seed-coats lying in little

heaps around these flowers: the work of that nocturnal

and big-eared creature, the wood mouse, which has an

appetite for juicy fruit and buds, peas and beans, as

well, apparently, as for the hairy violet. As for ants,

a kind of symbiosis has arisen between them and the

violets' because they relish the oily seed-stalks, the

ants carry the seeds away, dispersing them among

anthills where the plants grow with abundance. Although

widespread in Britain, the hairy violet has become so

rare in the Burren, County Clare, Ireland, that it is

now a protected species.

The third of these native flowers is exquisite. The Teesdale

violet is minute: a tufted non-creeper, hairy all

over, it is described as an upland plant and rare in

Britain but fortunately it is distributed throughout

central Europe including parts of Norway, Corsica, the

Italian Alps, Macedonia and Central Asia; in North

America from Quebec to Alaska and south from Maine and

Oregon. And according to the Red Data Book: "This

perennial is known from eleven localities on open,

mossy, sheep-grazed turf or bare ground on limestone in

Yorkshire, Durham and Westmoreland...Though it appears

to be adequately protected now, threats exist from

collectors, because of its rarity and the proximity of

an easy access road in one area, and from the planting

of conifers." (That dread habit we have in Britain

of spreading sterility up and down our hills).

Anyone walking country lanes will have seen the common

dog-violet, a bluish-violet perennial with a paler

spur, concealed on banks or among last year's woodland

leaves. It flowers later than the sweet violet and the

early dog-violet and, as far as I'm concerned, all three

appear impossible to distinguish. But for those in the

know, with sharp eyes and the inbuilt habit of looking

where they walk, this trio, unless they've hybridized

from close proximity, can be sorted out by the shape and

colour of the spurs, whether they have runners (which

this one hasn't) and from the form of leaves, sepals and

stipules.

The fifth in this list is the early dog-violet,

another non-creeper distinguished from the common violet

by having paler, "fly-away" petals giving it

an alert, listening look. And whereas in the common

dog-violet the spur is cream tinged with violet, here

the spur is darker than the petals. In England it's

everywhere: hedgebanks and woods, on limy or chalky

soils, but curiously it is only sprinkled about Wales

and Ireland and rare in Scotland.

The heath dog-violet, with short creeping

rhizomes, is a very blue species with a yellowish spur,

found growing in acid grassland, fens or on heaths.

The seventh flower is enchanting. Milky-coloured and

ghostly, this noncommittal pale dog-violet has

leaves often tinged with purple, adding to its unearthly

quality. Growing in scattered localities on dry heaths

in Anglesey and Pembroke, Sussex, Essex and often in

southwest England, the flower is also found in parts of

Ireland. On the Gower peninsula in south Wales Jo Dunn

hunted it down on cliff-tops, surprised to find it

growing so close to the sea.

The fen violet, V. persicifolia

(which descriptively means "with leaves like those

of the peach tree" and was called persica

malus by Pliny), is a beautiful flower a breath

away from vanishing. Rare! Endangered! Vulnerable! What

other adjectives carry such dire forebodings? The

flower, looking as frail as its tenuous fingerhold on

life, with hairline veins on the underside of its

duck-egg blue petals, a pure white throat, a greenish

spur and notched leaves, blooms in May and June in the

fens of Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, and among damp

grassy hollows on the limestone of western Ireland from

Fermanagh to Clare. Hounded from the fens by drainage,

chivvied into its one remaining habitat on newly

disturbed peat in Huntingdonshire, the fen violet has

triumphantly reappeared, after sixty years' absence,

among the peat diggins of Cambridgeshire. And in

Ireland, because it grows near the turloughs - those

strange lakes with fluctuating water levels that lie

among limestone rocks - it's known as the turlough

violet. Thankfully in other parts of the world this

endearing little creeping herb still exists.

The marsh violet has a delicate face. Pale lilac

with darker honey guides spread across the petals like a

delta, the plant lives up to its squelchy name by

perpetuating itself with creeping rhizomes in bogs,

marshes, fens and wet heaths.

The next five are pansies. It is impossible not

to gush over their expressive faces.

"Adorable" sounds sickening, but that is how

they look. Each is a winning as the last. Enjoyment,

surprise, alertness, reticence or self-deprecation -

they reveal it all.

Though the plants are small --some often skulk among

leaves or tufty grasses- differences in appearance and

habit make it easy to distinguish the wild pansy from

the violets. The latter, which must painstakingly be

searched for are synonymous with modesty, shyness and

all those fairly low-key attributes that have long been

associated with this flower. And while two of the

pansies may be said to possess such qualities, the other

three (including a subspecies)--the mountain, wild and

dune pansies--though they could never be called

immodest, are relatively bolder. As their names suggest,

they go in for a more open lifestyle. Although they

share with the violet nectar-filled spurs and radiating

honey guides on their petals, pansy flowers differ in

having flat, more rounded faces which, in most cases,

are larger and more vividly coloured; and while pansy

leaves aren't dissimilar from those of violets, their

stipules are distinctive, being leaflike and deeply

lobed.

If appearance were all, then you only need to look at

the beautiful, enquiring face of a bright yellow or

violet-coloured mountain pansy to realize that

this is where demureness all but vanishes and a hint of

showiness begins. No wonder the cultivation of many

strains of our garden pansies started here.

The mountain pansy is bright yellow but

occasionally, to baffle you, the flat flowers may be

purple or blotched, arbitrarily lined with honey guides

on its naive and cheerful face. The flower grows in

upland, often calcium-deficient grassland, and on rocky

ledges in every country north of a line between the

Humber and the Severn.

Some modern garden pansies have evolved from hybrids

between this one and heartsease. According to which way

you face, show and fancy pansies have been its ultimate

fate or triumph.

Now we come to heartsease whose name ought to shower us

with blessings. The wild pansy, V. tricolor,

appears everywhere there are recording enthusiasts, in

the garden or in the wild: "It groweth often among

the corne," wrote William Turner in 1548. And it

still does. Deep purple, light mauve, yellow or

combinations of these, this flower seeks acid, light or

sandy waste ground, rarely in the south and then only on

mountains. Judging by the long list of local names with

love and kiss in them, this plant provokes particularly

endearing associations. To name a few: Love-in-Idleness,

Leap-up-and-Kiss-Me and Kiss-me-Love-at-the-Garden-Gate

speak of a rural idyll well suited to a retiring flower

known as heartsease. Oberon, in A Midsummer Night's

Dream, squeezed the juice from Love-in-Idleness into

the eye of Titania so that on waking she would fall in

love with Bottom. Why it should have so many love names

is not clear, but in contrast to this jolly wantonness

the herb also has a pious image: thought by some to have

the appearance of three faces under a hood, it is also

known as "Trinitatis herba" --the Blessed

Trinity flower.

Among the monumental range of research undertaken by

Darwin during his long lifetime (which included a study

of the life cycle of earthworms), he studied the way

transplanted heartsease so instantly changed colour and

markings, and yet could return to their original colours

before the end of the summer. Such capriciousness was a

bane and a boon. In the wild, in different soil and

climatic conditions, identifying Viola species could

become very hit-and-miss. On the other hand heartsease,

with agreeable facility, could breed a whole chiaroscuro

of offspring. The violet family are apt to lose their

head when it comes to procreation, and crossbreed

avidly, which accounts for the numerous progeny of

pretty hybrids that turn up in our gardens, their

parentage unrecorded until it is too late for the

botanist intent on nomenclature. Even in the gardens of

Buckingham Palace, Dr. David Bellamy has discovered

three vagrants: the common dog-violet, the field pansy,

and, let's hope it works, heartsease.

The dune pansy (V. Subsp. Curtisii),

is almost like a small mountain pansy. Yellow,

blue-violet or parti-coloured, this perennial has

flowers with such stand up petals it has a prick-eared

expression which is most appealing. By adapting to

inhospitable terrain it grows in dunes and grassy places

close to the sea in parts of Britain, as well as the

chilly shores of the Baltic.

The twelfth and most self-effacing of the lot is the field

pansy. Usually a yellow as pale as clotted cream,

this annual is commonly found on cultivated or waste

ground in Europe or as remotely far flung as in Siberia,

Iran, Iraq, and North Africa. "This is one of the

arable 'weeds' which has resisted elimination by modern

herbicides," says Jo Dunn. "When the capsules

explode, the seeds may be spread as far as two metres."

Luckily, these tactics help to ensure that the plant

survives But only those partial to bending over as they

walk the countryside would have the engrossed patience

to notice the flower as Jo does. As she succinctly

remarks: "It's a small, rather overlooked pansy,

which needs to have a hand-lens focused on its face

before it can be appreciated!"

The last of the tribe is the dwarf pansy: a very

rare annual with a hooded cream or pale violet face, its

flower is minute, sometimes no more than 1 inch in

height, but it has great charm. Jo Dunn admits she has

only seen this pansy once, by crawling on hands and

knees with a lens at the ready: "I marvelled that

anything so small could survive!" according to the

ominous and somewhat puzzling words of the Red Data

Book, it "will be endangered only if digging for

sand ceases and rabbits become extinct." For unlike

so many wild and garden plants - it thrives on

disturbance.

Whether grown from seed or by division the full range of

violaceae for the garden means you have your hands on an

infinity of variations. The colour range is past

defining; so many of the species of Viola from all over

the world, not just the thirteen I've listed here, have

produced superb cultivars.